Early 1991 - fuck me this is a lineup I would have liked to have caught, even in the poky rock venue confines of Subterania. Sub-lo frequencies surely sufficient to shake the foundations of the Westway flyover.

And here is a review of the concert by Melody Maker's Ian McGregor, from March 30 1991

He was big into the bleep n bass sound - from the very same issue of MM, here's McGregor's review of Sweet Exorcist's C.C.E.P. - deservedly treated as a mini-LP rather than just an EP

And here from almost a year earlier is McGregor reporting on a iD magazine team-up with Warp, "one of the fastest growing hardcore dance labels around".

Bleep was young Ian's beat pretty much.

'

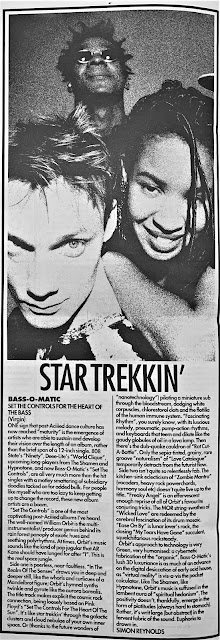

This sort of content is one of the reasons the idea of MM as an Indie Paper annoys me. (Apart from anything we had as almost much major label rock covered as indie chart stuff, and kept an eye on metal!). But more to the point I'm trying to make: there was a lot of hip hop covered, and some R&B too, and a bit of reggae, and even some jazz and experimental music. And there was a lot of dance coverage. During this same 89-90-early91 period, although not an active raver yet, I'd be reviewing singles by such as DHS and Eon when I did the single's column, or raving about albums by 808 State and Bass-o-matic. Others on the paper would be doing Gerald or Shut Up and Dance or Unique 3s as well as your Flukes i.e. ostensibly more rock-paper friendly stuff. (The exact same could be said for NME and also Sounds albeit probably more so earlier in its history than the '90s).

Conversely, it's not like Mixmag or DJ (or Black Echoes and Blues & Soul for that matter) were covering the cutting edge of underground rock at this time! The imperative of comprehensiveness and inclusion fell only on the shoulders of the rock press. And was actually shouldered, fulfilled to a remarkable degree. In a relatively routine, this-is-what-we-do sort of way. Driven by the writers and editors's enthusiasms, as well as a vague sense that it was the right thing to do. (When in truth, the majority of the readership would have been happy not to have all this stuff in there, would in fact have been okay with homogeneity.)

It's worth noting also that a few years later an entire monthly dance music magazine, Muzik, was essentially spawned out of the dance section in Melody Maker, by MM writers Push and Ben Turner.

In fact, looking at the coverage amassed below (to which I keep adding), I'd venture that - alongside all the other stuff covered in the magazine, MM actually had better coverage of dance music and electronic music than the specialist magazines of that time. Okay, not as comprehensive (although with four issues a month c.f. one issue for the dance monthlies, it wasn't that far off) but certainly more astute / acute / acerbic and vividly written, coming as it did from a tradition of writing-as-writing and from the slag-off as artform.

Derrick May and Kevin S's sniffy dismissals of ardkore as a bassturdizing betrayal of the Sacred Source set me up for this Bangsian counter-move a fortnight later - a trash aesthete transvaluation of ephemeral drug-noise (still too much of an apologia, but I would become more confident in my preferences as the year unrolled).

RRRRRRUSH! : Hardcore Rave and London Pirate Radio

Melody Maker, July 4th 1992

Two weeks ago, Detroit techno pioneers Derrick May and Kevin

Saunderson were whining in Melody Maker

about how UK

hardcore is a grisly bastardisation of their vision of techno. And it's true

that the austere, elegantly minimalist music made by May and his fellow

Europhiles, has virtually nothing to do with the riotous uproar of hardcore. But far from being 'bastardised', the truth

is that just as with acid house back in '88, the term 'techno' became detached

from its American prototype, and mutated into a totally different animal.

Hardcore is the latest in a long line of great British remotivations of Black

American music.

Hardcore only really makes full

(non)sense amidst the Dionysian tumult of an illegal rave (otherwise, it's like

a soundtrack divorced from its movie). But you can get an idea of the vibe by

tuning into London's

pirate hardcore stations like Rush FM, Pulse, Destiny, and Touchdown. (They

also provide an opportunity to tape the latest, obscurest tracks for

free). Self-styled "'ardcore

station for the 'ardcore nation", Touchdown seems to be the most regular and

have the strongest signal (94-1 FM). From Friday eve to Monday morn, it

provides a relentless soundtrack to vibing up before going out, driving between

clubs, and recuperating afterwards.

Where the Detroit and early UK

techno units like LFO/Orbital/808 State, were relatively musically skilled and programmed

their own rhythms etc, hardcore is real DIY barbarianism, cobbled together from

looped, insanely accelerated breakbeats, asininely simplistic keyboard riffs, dub

basslines, and samples of ecstatic vocals sped up to 78 rpm (the ethereal

girl-vox of This Mortal Coil, Kate Bush, Dead Can Dance, Pinky & Perky

shrieks of soul euphoria, ragga incantations). In isolation, few tracks stand

up to intense scrutiny; it's together, as a "total flow", that they

take effect. The feeling is like being plugged into the National Grid. The MCs' staccato patter - "'ere we

go!", "let's get rough", "rrrrr-rush!" all becomes

part of the flow. As if the individual

tracks weren't crudely collaged enough already, the DJ's mix in rough-and-ready

bursts from other records, creating an inexhaustible, interminable meta-music

pulse.

No songs here: the keyboard motifs

are trite, what hooks you is the timbre of a synth-tone, the colon-deep

consistency of a bass-line, the epileptic spasm of a beat. Like avant-garde music, hardcore spurns

melodic development in favour of repetition, drones, atonal sonorities, found

sounds etc. But hardcore's a sort of

degraded avant-gardism, an arrested futurism.

And that's what's so weird about it: the ideas and effects of DAF, Die

Krupps, Cabaret Voltaire etc, have become pop in the most low-com-denom,

plebeian sense.

Most hardcore is trash, then, but

it's effective trash. Techno's

developed beyond music and into a science of inducing and amplifying the

Ecstasy rush. The sound is all subsonic bass and ultra-trebly shrillness,

bowel-tremor and spine-tingle. Hardcore

is a techno-pagan cult dedicated to the worship of speed: not just high b.p.m,

but the amphetamine that most E tablets largely consist of these days. With

group names like Risla Bass and song titles like "We Are E", hardcore

must be the most blatantly druggy subculture since acid rock; DJ's call out to

"all you nutters rushing out of your heads, speedfreaks out there, you

know the score", send out a "big shout to everyone who's absolutely

trippin' in Hendon", or talk about how they're "absolutely flying in

the studio, 100 m.p.h.".

"Let's go" chants the DJ, but this is an intransitive

acceleration, without destination. "Hold tight", he'll cry, like

you're on a rollercoaster (and apparently, techno is all you'll hear at funfairs

these days). Where Detroit

techno was spiritual, hardcore is purely about sensation, about an artificially

induced state of hyper-real intensity (or, as the title of one track has it,

"Hypergasm").

Crude, mindless, but it's the most

vibrant subculture around, and as addictive as crack.

^^^^^^^^^^^

wot's all dis then? in the very same issue as my ardkore manifesto, there is a reader's letter in Backlash that is an early sighting of certain Punctum-pursuing blogger-to-be and who here is singing from the very same psalm book as me! Complete a retort from defender of Lyrics Jim Arundel, editing the letter's page that week

Not actually MM (this is from NME) but here is Derrick May doing the rounds with his 'techno's gone to shit' moaning, and hats off to the NME editor who came up with this headline: I Piss On Your Rave.

Back to MM...

David probably speaks here for the majority view at

Melody Maker at that time - we can't cover this stuff much more than we do because it's hard to cover. But I think this view was mistaken: we'd already written about

Mantronix and Nitro Deluxe et al in appropriately posthumanist and non-rockist terms, New Sonic Architecture, when it was required to do so; the paper had for some time been covering the rave scene thoroughly and writers would increasingly find ways of writing about technotronic sounds truer to its nature as an abstract play of forces and tones, a battery of sensations and energies. Equally, within the emerging electronic field there would turn out be Personalities with Ideas and Things To Say - Weirdos and Characters just as much as any indie rock outfit and possibly more so. Indeed, there would soon be Pretensions (metaphyiscal and otherwise) abroad in the electronic field that would far outstrip most indie bands of the '90s.

Before all of this, of course, MM was the rave paper because it covered the original rave scene - trad jazz